Capt. Ray Arntz assisting John Walker (left) and Kendall

Raine

before their first dive to the B-36 Peacemaker.

Photo by Pat Macha.

B-36

Dive Report

By Kendall Raine

December 2008

The weather was perfect after two weeks of storms. A warm

orange glow built from the east and the sea had a small

rolling swell. We left Mission Bay aboard

Sundiver II early

for the run out to the site of the crash of the largest

combat aircraft ever built. Nicknamed the Peacemaker,

the Convair B-36 was the first strategic bomber in the

American arsenal. In its day, no other aircraft of any

nation could fly as far with as large a payload as the

B-36. Conceived during World War II as a massive

conventional bomber, it was well suited to its early

cold war role as the ultimate deterrent against a Soviet

nuclear threat.

Despite claims since 2004 that the aircraft had been

located and dived by others, no evidence had ever been made

public supporting such claims. Dive reports from others

made us suspicious that what others were calling the B-36

was a rock pile with some scattered debris of something,

but not a massive aluminum and magnesium bomber. Based upon

our skepticism, we undertook a new search for the elusive

plane.

Once our team reviewed drop camera images of one of our

targets in October, we knew we had identified the wreck

site and that previous descriptions of the wreck’s

condition, it’s location and bottom features were

erroneous. We believed we would be the first sport divers

to visit her last resting place.

Aboard Sundiver was Captain Ray Arntz, aircraft

archaeologist Pat Macha, John Walker and I. John and I were

extremely excited about this dive. Having established the

wreck’s location six weeks ago, we’d been

chomping at the bit for a chance to visit the wreck.

Aircraft archaeologist G. Pat Macha.

We arrived on site and dropped a weighted line in what we

believed was the center of the debris field. We knew the

wreck was severely broken up. We also expected substantial

portions of the fuselage and wings outer skin to have

corroded away. While the aluminum skin would have survived,

much of the B-36 covering was of magnesium. A revolutionary

material in 1952 terms of strength to weight ratio,

magnesium burned very easily and corroded very rapidly in

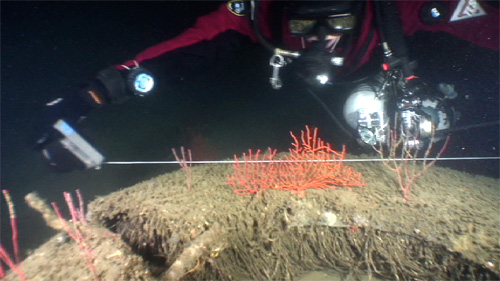

salt water. At the depth of the wreck, our scouting range

would be limited and swimming any distance at this depth

would bring the added penalties of increased gas

consumption and decompression stress. Our objective for

this dive was to shoot video of as many clearly

identifiable features of the B-36 as possible. First

amongst those would be the massive tires and propellers of

the B-36 who’s proportions were so beyond any other

aircraft then or now as to make identity a certainty. As

such, we expected to limit our swim to the area around the

middle of the massive aircraft so as to maximize our

chances of locating these features. We had drop camera

images of both targets, but scale was needed to make

identity definitive.

John and I descended the weighted line. We hoped for

similar conditions to those of our previous trip, but the

bottom was very dark. Visibility was no more than 15 feet

and a slight current ran over the wreck. I tied in a reel

to the up line and swam on a heading of 240 degrees toward

what we believed would be the middle of the fuselage. John

swam ten feet away to my left, the twin 35 watt HID lamps

of his video throwing a large field of light over the

wreck. From the beginning it was shocking how shattered the

wreckage was. The fuselage was flattened and broken in so

many pieces the largest section was perhaps fifteen feet

long. Despite this, I quickly passed over a large circular

opening in the top of the fuselage which was probably one

of the sighting blisters.

A hole in the aircraft skin where a plexiglas sighting

blister used to be installed.

Wiring ran the direction of our swim suggesting we were

following the contour of the fuselage. Almost everywhere

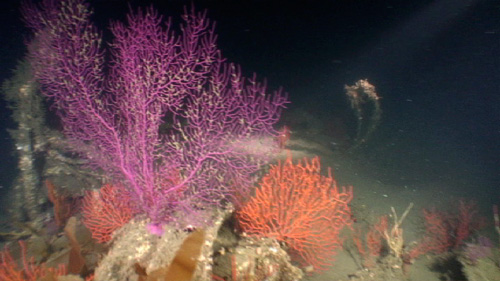

our lights illuminated vibrant purples, reds, oranges and

green gorgonians.

Beautiful gorgonians are abundant on the wreck.

Bright colored rock and flag fish scattered as we intruded

upon their home. After a five minute swim we came to a

patch of sand with no visible wreckage beyond. I turned

around and began to reel up the line. As I swam I noticed

mounds of debris off to my left. A dome shaped object

appeared in the darkness. It was semispherical except that

a portion of the dome was caved in. Though encrusted, the

dome looked to be made of plastic. Closer examination

revealed an aluminum base with handles visible protruding

from the bottom. This could only be one of the sighting

blisters used as part of the plane’s defensive system

and for observation/navigation-it fit in the hole in the

fuselage seen earlier. The dimensions and characteristics

of this object matched perfectly those of the B-36.

(Left) A plexiglas sighting blister from the last B-36

Peacemaker at the Pima Air & Space Museum, Tucson, AZ.

Photo by Gary Fabian. (Right) A damaged sighting blister

from the wreck site of the B-36 Bomber. Photo by John

Walker.

Continuing left, I came across more and more solid chunks

of aircraft including what looked like massive wing spars.

Large sections of rubber protruding from these spars

suggested portions of the fuel cells. As there was no

evident fire damage, I assumed I was over the left wing. My

suspicions were soon confirmed as out of darkness loomed

what was obviously one of the main landing gear struts. Its

massive length and diameter matched photographs. I looked

for the four massive tires which had to be nearby. The

first pair of these soon came into view. Nearly five feet

in diameter, these tires were the largest on any aircraft

of its time and rival those of today’s largest

commercial aircraft. They lay one on top of the other with

part of the wheel axle protruding from the top tire. I

immediately signaled John to shoot the image. As John and I

swam forward a few more feet another tire came into view.

With John”s light illuminating the scene I stretched

my arms wide across the diameter of the tire. My guess at

the time was that the diameter exceeded five feet. These

could not belong to any other aircraft known to have

crashed off Mission Beach.

Kendall Raine swims past a pair of landing gear tires. An

axle can be seen protruding from the center of the tires.

Photo by John Walker.

Kendall taking a measurement of another B-36 tire. Photo by

John Walker.

I then began a search for one of the six turbo charged

pusher mounted engines. What I really wanted was to get

scale on a propeller. Our bottom time was almost up and we

needed to turn for the up line. As we reached the up line I

cut the guideline from my reel rather than wasting time

reeling up. The penetration line was tied into the up line

and Ray would pull the whole mess up as he retrieved the up

line.

John and I started our long slow ascent back to light and

warmth. As we settled into the familiar routine of

decompression stops and gas switches, I shot a lift bag so

as to allow Ray to retrieve the up line. We completed our

deco drifting.

Ray and Pat eagerly welcomed us back. We quickly got back

aboard and loaded the video into Ray’s monitor. Pat

was fascinated with the video. Having spent much of his

adult life searching for and identifying military airplane

wrecks, Pat was able to offer possible identification to

numerous pieces of wreckage evident on the video. His

knowledge of the B-36 was nearly encyclopedic. When he saw

the landing gear struts and the sighting blister the case

was sealed. Seeing me draped over the tire was just icing

on the cake.

There is no doubt this was the wreck of a Convair B-36. The

only one to have crashed off Mission Beach and the plane so

heroically piloted by Dave Franks in those final minutes as

he bought with his life precious time for his crew to bail

out.