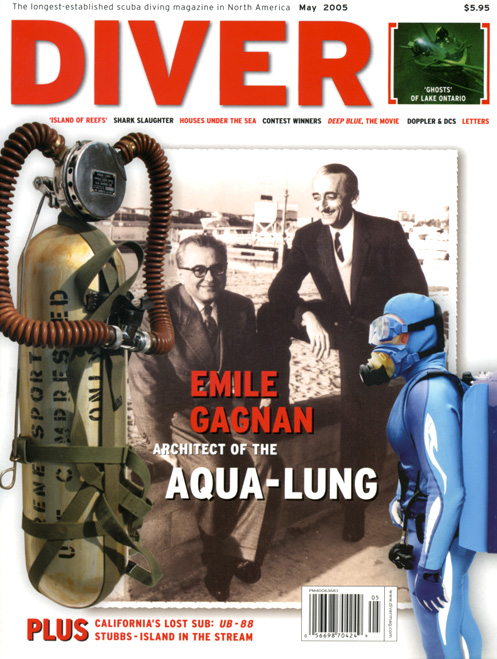

Diver Magazine, May

2005 Issue

Reprinted with permission

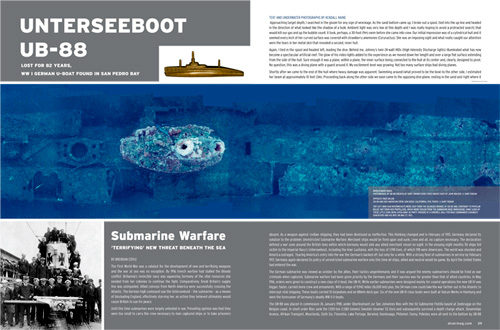

UNTERSEEBOOT

UB-88

LOST

FOR 82 YEARS, WWI GERMAN U-BOAT

FOUND IN SAN PEDRO BAY CALIFORNIA

Submarine

Warfare

‘TERRIFYING’ NEW THREAT BENEATH THE SEA

BY BRENDAN COYLE

The First World War was a catalyst for the development of

new and terrifying weapons and the war at sea was no

exception. By 1916 trench warfare had stalled the bloody

conflict. Britannia’s invincible navy was squeezing

Germany of the vital resources she needed from her colonies

to continue the fight. Comparatively, Great Britain’s

supply line was unimpeded. Allied convoys from North

America were successfully crossing the Atlantic. The German

high command saw the Unterseeboot – the submarine

– as a means of blockading England, effectively

starving her, an action they believed ultimately would

cause Britain to sue for peace.

Until this time submarines were largely untested in war.

Prevailing opinion was that they were too small to carry

the crew necessary to man captured ships or to take

prisoners aboard. As a weapon against civilian shipping,

they had been dismissed as ineffective. This thinking

changed and in February of 1915, Germany declared its

solution to the problem: Unrestricted Submarine Warfare.

Merchant ships would be fired upon and sunk, crew and all,

no capture necessary. The declaration defined a war zone

around the British Isles within which Germany would sink

any allied merchant vessel on sight. In the ensuing eight

months 50 ships fell victim to the Imperial Navy’s

Unterseeboot, including the liner Lusitania, with the loss

of 1,198 lives, of which 198 were Americans. The world was

shocked and America outraged. Fearing America’s entry

into the war the German’s backed off, but only for a

while. With a strong fleet of submarines in service by

February 1917, Germany again declared its policy of

unrestricted submarine warfare only this time all ships,

allied and neutral would be game. By April the United

States had entered the war.

The German submarine was viewed as sinister by the allies,

their tactics ungentlemanly and it was argued the enemy

submariners should be tried as war criminals when captured.

Submarine warfare had been given priority by the Germans

and their success was far greater than that of allied

countries. In May 1916, orders were given to construct a

new class of U-boat, the UB-III. While earlier submarines

were designed mainly for coastal operations the new UB-III

was bigger, faster, carried more crew and armaments. With a

range of 9,942 miles (16,000 km) plus, the 34-man crew

could take the war farther out in the Atlantic to intercept

vital shipping. These boats carried 10 torpedoes and an

88mm deck gun. Six of the new UB-III class boats were built

at Vulcan Werks in Hamburg and were the forerunner of

Germany’s deadly WW II U-boats.

The UB-88 was placed in commission 26 January 1918, under

Oberleutnant zur See Johannes Ries with the 1st Submarine

Flotilla based at Zeebrugge on the Belgian coast. In short

order Ries sank the 1,555-ton (1,580 tonnes) Swedish

steamer SS Dora and subsequently survived a depth charge

attack. Steamships Avance, Afrikan Transport, Moorlands,

Sixth Six, Florentia, Lake Portage, Berwind, Hundvaago,

Philomel, Fanny, Polesley were all sent to the bottom by

UB-88 for a total of 32,340 tons (32,850 tonnes) over her

short war service of five patrols. She survived five known

counter-attacks. The sub damaged the freighter Anselma and

was partially responsible for damage inflicted to the

British steamer Bayronto when a torpedo fired from a French

destroyer missed the U-boat and struck the allied ship.

Following the end of hostilities on November 11, 1918,

UB-88 surrendered at Harwich, England, on November 27,

1918, where she was moored and her crew interned. On March

13, 1919, six German U-boats of various classes, among them

UB-88, were allocated to the United States Navy by the

British Admiralty for research and use in the

‘Victory War Bond’ drive. Under the American

flag and manned by a U.S. navy crew, UB-88 departed Harwich

on April 3 and arrived in New York April 27, 1919. During

her extensive tour of the United States UB-88 made calls to

ports along the Atlantic coast, the Gulf of Mexico, the

Mississippi River, the coast of Panama while transiting the

canal, and along the U.S. west coast as far north as

Seattle, Washington, steaming a total of 15,361 miles

(24,720km). Forty-five cities were visited, and over

400,000 visitors were shown through the boat before she

made her final destination November 9, the San Pedro Naval

Yard in California. The once formidable hunter was

decommissioned November 1, 1920, and stripped of most

machinery and fittings. On January 3, 1921, UB-88 was towed

to an area off Los Angeles in San Pedro Bay and (in

accordance with WWI peace treaty terms) was sunk by gunfire

from the destroyer USS Wickes, whereupon she disappeared

for 82 years.

Long the dream of many Los Angeles-area divers to find

UB-88, the antique submarine eluded discovery until local

sport fisherman Gary Fabian took an interest. A non-diver,

Fabian partnered with long time dive boat operator Ray

Arntz, who had also been searching for the elusive sub. The

pair had completely differing views on where the sub might

be located. Fourteen months of weekend searches culminated

July 9, 2003, when Fabian registered a positive

‘hit’ with his fish-finding sonar. (((the

high-resolution digital imagery provided by the U.S.

Geological Survey (see sidebar))) When drop camera video

footage confirmed the hit was, indeed, a wreck, the search

team expanded, initially to include technical divers

Kendall Raine and John Walker, and later Scott Brooks and

Fred Colburn.

Sonar indicated the wreck was reasonably intact and on

August 27, Raine and Walker made the initial dive, becoming

the first to lay eyes on UB-88 (to the best of

everyone’s knowledge) since her sinking 82 years

earlier. A slender, preserved hull, diving planes, torpedo

tubes conning tower, two shell holes from the USS

Wickes’ four-inch deck gun and a measured length of

190 feet (58m) and 19-foot (5.75m) beam confirmed the wreck

to be the elusive UB-88 (see accompanying story). Fabian

has not revealed the location or depth of UB-88 but says

she is well beyond the range of sport diving.

Before being scuttled, the submarine was stripped of most

fixtures. Much of the nautical brass fittings usual on a

wreck of this vintage were manufactured from steel out of

wartime necessity. The brass props were removed before her

sinking (see sidebar). Inside the wreck is a 25-pound cache

of TNT intended to sink UB-88 had the shellfire proved

ineffective. The shells did the job, however, one of them

severing the cable link between the submarine and a

stand-by vessel, preventing detonation of the high

explosives had it been necessary.

UB-88 was an advanced weapon in mankind’s first

‘global’ conflict. The U.S. Navy learned a

great deal about German submarine technology from her and

much of that knowledge played an important, perhaps

decisive, role in the development of the highly successful

American submarine force of the Second World War.

Meanwhile, UB-88 lies in state – her gray wartime

paint replaced by orange and strawberry anemones, rockfish

lulling in and out of the torpedo tubes that wrought the

death of 13 merchant steamers – a haunting relic of

the Great War.

The author and Diver Magazine thank Gary Fabian and Kendall

Raine for their assistance in presenting this story.

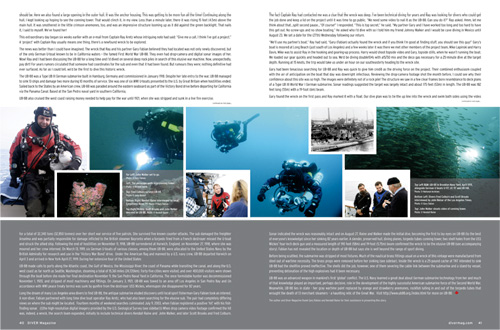

TEXT AND

UNDERWATER PHOTOGRAPHS BY KENDALL RAINE

Approaching target depth, I searched in the gloom for any

sign of wreckage. As the sand bottom came up, I broke out a

spool, tied into the up line and headed in the direction of

what looked like the shadow of a hulk. Ambient light was

very low at this depth and I was really hoping to avoid a

protracted search; that would kill our gas and up the

bubble count. It took, perhaps, a 30-foot (9m) swim before

she came into view. Our initial impression was of a

cylindrical hull and it seemed every inch of her curved

surface was covered with strawberry anemones (Corynactus).

She was an imposing sight and what really caught our

attention were the tears in her metal skin that revealed a

second, inner hull.

Again, I tied in the spool and headed left, leading the

dive. Behind me, Johnny’s twin 24-watt HIDs (High

Intensity Discharge lights) illuminated what has now become

a spectacular artificial reef. The glow of his video lights

added to the experience as we moved down her length and

over a large flat surface extending from the side of the

hull. Sure enough it was a plane, within a plane, the inner

surface being connected to the hull at its center and,

clearly, designed to pivot. No question, this was a diving

plane with a guard around it. My excitement level was

growing. Not too many surface ships had diving planes.

Shortly after we came to the end of the hull where heavy

damage was apparent. Swimming around (what proved to be the

bow) to the other side, I estimated her beam at

approximately 10 feet (3m). Proceeding back along the other

side we soon came to the opposing dive plane, resting in

the sand and right where it should be. Here we also found a

large opening in the outer hull. It was the anchor housing.

This was getting to be more fun all the time! Continuing

along the hull, I kept looking up hoping to see the conning

tower. That would clinch it, in my view. Less than a minute

later, there it was rising 15 feet (4.5m) above the main

hull. It was smothered in the little crimson anemones, too,

and was an impressive structure looming up as it did

against the green backlight. That nails it, I said to

myself. We’ve found her!

This extraordinary day began six weeks earlier with an

e-mail from Captain Ray Arntz whose intriguing note had

said: “Give me a call, I think I’ve got a

project.” A ‘project’ with Captain Ray

usually means one thing, there’s a newfound wreck to

be explored.

The news was better than I could have imagined. The wreck

that Ray and his partner Gary Fabian believed they had

located was not only newly discovered, but of the only

German U-boat known to be in California waters – the

famed First World War UB-88. They even had drop-camera and

digital sonar images of her. Wow! Ray and I had been

discussing the UB-88 for a long time and I’d dived on

several deep rock piles in search of this elusive war

machine. Now, unexpectedly, pay dirt! For years rumors

circulated that someone had coordinates for the sub and

even that it had been found. But rumours they were; nothing

definitive had ever surfaced. As far as I could tell,

we’d be the first to dive this historic wreck.

The UB-88 was a Type UB III German submarine built in

Hamburg, Germany and commissioned in January 1918. Despite

her late entry to the war, UB-88 managed to sink 13 ships

and damage two more during 10 months of service. She was

one of six WWI U-boats presented to the U.S. by Great

Britain when hostilities ended. Sailed back to the States

by an American crew, UB-88 was paraded around the eastern

seaboard as part of the Victory Bond drive before departing

for California via the Panama Canal. Based at the San Pedro

naval yard in southern California, UB-88 also cruised the

west coast raising money needed to help pay for the war

until 1921, when she was stripped and sunk in a live fire

exercise.

The fact Captain Ray had contacted me was a clue that the

wreck was deep. I’ve been technical diving for years

and Ray was looking for divers who could get the job done

and keep a lid on the project until it was time to go

public. “We need some video to nail it as the UB-88.

Can you do it?” Ray asked. Hmm, let me think about

that...split second pause...“Of course!” I

responded. “This is top secret,” he said.

“My partner Gary and I have worked too long and too

hard to have this get out. No screw-ups and no show

boating.” He asked who I’d dive with so I told

him my friend Johnny Walker and I would be cave diving in

Mexico until August 23. We set a date for the (27th)

Wednesday following our return.

“We’ll use my partner’s boat,” Ray

had said, “Gary (Fabian) actually found the wreck and

if you think I’m good at finding stuff, you should

see this guy!” Gary’s boat is moored at Long

Beach (just south of Los Angeles) and a few weeks later it

was there we met other members of the project team, Mike

Lapinski and Harry Davis. Mike was to assist Ray in the

hooking and gearing-up process. Harry would shoot topside

video and Gary, topside stills, when he wasn’t

running the boat. We loaded our gear quickly and headed out

to sea. We’d be diving double 104s with a15/50 mix

and the deco gas necessary for a 25-minute dive at the

target depth. Running at 15 knots, the trip would take us

under an hour on our southeasterly heading to the wreck

site.

Gary had been tenacious searching for UB-88 and Ray was

quick to give him credit as the driving force on the

project. Their combined enthusiasm coupled with the air of

anticipation on the boat that day was downright infectious.

Reviewing the drop-camera footage shot the month before, I

could see why their confidence about this site was so high.

The images were definitely not of a rock pile! The

structure we saw in a few clear frames bore resemblance to

deck plans of a Type UB III World War I German submarine.

Sonar readings suggested the target was largely intact and

about 175 feet (53m) in length. The UB-88 was 182 feet long

(55m) with a 19-foot (6m) beam.

Gary found the wreck on the first pass and Ray marked it

with a float. Our dive plan was to tie the up line into the

wreck and swim both sides using the video recorder to

capture signifying marks along the way. I would lead, run

lines and spot the video targets. John would operate the

camera and use his new Halcyon lights to ensure the

fidelity of our photographic recon.

If the conning tower was intact we especially wanted a

clear video record of that but we weren’t sure what

to expect because action reports from the day she was sunk

suggested her ‘sail’ might have been destroyed

during the live fire exercise. Now we knew the truth. That

didn’t happen! While Johnny got busy I needed to

answer a nagging question so I ascended the side of the

conning tower to inspect its top and there, to my great

pleasure, was what I had hoped to see: two holes about four

inches (10cm) in diameter and three feet (.9m) apart

– periscope wells! Bingo. If I harboured any doubts

about this being UB-88, they were gone now. Suddenly, the

gloom around me blazed into colour. Heeeeere’s

Johnny. I pointed at the periscope wells with my light and

then moved out of the shot. In front of these appeared to

be the hand wheel of a hatch cover.

With that important goal accomplished, we swam back down to

the hull and continued heading aft. Behind the conning

tower were two hatches, their hand wheels heavily encrusted

but still clearly identifiable. Here, we could clearly see

the groove formed by the junction of the pressure hull and

ballast tanks. We also found a hole penetrating the

pressure hull. Cool! I shined my light into the interior of

the sub but couldn’t really see anything. Further

back I came upon a large net caught in the wreckage but

hanging off the hull by its fl oats. It must have been

there a long time because it was very old. Dropping behind

the net I found myself at the stern. A steel rail

originally attached here now lay in the sand and was

further evidence our find was the UB-88. The rail appears

in the deck plans and is unique to Type UB III boats.

Swimming around to the port side of the wreck, I was able

to make out propeller shaft struts and the flange into the

hull. The shafts and propellers had been removed in San

Pedro Navy Yard prior to sinking. Johnny was right behind

me recording for the guys topside everything our eyes were

taking in. I just knew Ray and Gary would be happy with

this video. I continued forward and examined various places

where the outer hull had been breached, exposing the

pressure hull. Finally, my submarine circumnavigation

brought me back to our starting point and the bow plane.

Now, for the first time, I noticed a torpedo tube exiting

the pressure hull. I motioned to Johnny to film it and not

too soon because our time was up.

After an hour of deco John and I surfaced. An eager

‘Gary & Co.’ picked us up and we wasted

little time playing the video. It was spectacular and a

confirmation for all that the object of a two-year search

in archives and across miles/kilometers off San Pedro Bay

had ended in success. Without doubt it was a submarine and

we’d identified enough design features to say,

unequivocally, she was a Type UB III boat.

We were an excited bunch! The ride in was spent discussing

many aspects of what we’d seen and also plans to

document the find. Since that day of discovery additional

dives have been made to further document the wreck. Gary

and Ray will not disclose the location because the

possibility of unexploded satchel charges (ordnance)

remaining inside the wreck, coupled with her depth and

entanglement hazards, make the UB-88 a very hazardous

proposition even for experienced technical divers. In 1921,

preparations to sink her took four months so it’s

unlikely that many interesting artifacts remain.

Nevertheless, I was honoured to make this exploratory dive

confirming her location; it’s a treasured memory and

I’ve told that to Gary and Ray. There’s just

nothing like being the first to touch a lost wreck.

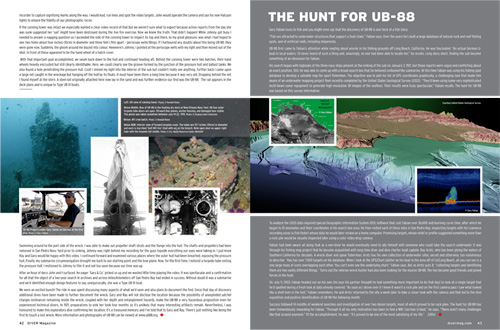

THE HUNT

FOR UB-88

Gary Fabian loves to fish and you might even say that the

discovery of UB-88 is one heck of a fish story.

“Fish are attracted to underwater structures that

support a food chain,” Fabian says. Over the years

he’s built a large database of natural rock and reef

fishing spots, and of artificial reefs, including

shipwrecks.

UB-88 first came to Fabian’s attention while reading

about wrecks in his fishing grounds off Long Beach,

California. He was fascinated. “An actual German U-

boat in local waters. I’d never heard of such a thing

and, amazingly, no one had been able to locate her,”

he recalls. Long story short, finding the sub became

something of an obsession for Fabian.

His search began with logbooks of the three navy ships

present at the sinking of the sub on January 3, 1921, but

those reports were vague and conflicting about an exact

position. Still, he was able to come up with a broad search

box that he believed contained the submarine. At this time

Fabian was using his fishing spot database to develop a

saleable map for sport fishermen. The objective was to plot

his list of GPS coordinates graphically, a challenging task

that made him aware of an underwater mapping project then

recently completed by the United States Geological Survey

(USGS). “They’d been using some very

sophisticated multi-beam sonar equipment to generate

high-resolution 3D images of the seafloor. Their results

were truly spectacular,” Fabian recalls. The hunt for

UB-88 was based on this survey information.

To analyze the USGS data required special Geographic

Information System (GIS) software that cost Fabian over

$6,000 and learning curve time, after which he began to ID

anomalies and their coordinates in his search box area. He

then visited each of these sites in San Pedro Bay,

inspecting targets with his Lowrance recording sonar (a

fish finder) whose data he would later review on a home

computer. Promising targets, whose relief or profile

suggested something more than a rock pile would be visually

inspected later using a color video drop camera.

Fabian had been aware all along that as a non-diver he

would eventually need to ally himself with someone who

could take the search underwater. It was through his

fishing map project that he became acquainted with long

time diver and dive charter boat captain, Ray Arntz, who

has been plying the waters of Southern California for

decades. A wreck diver and spear fisherman, Arntz has his

own collection of underwater sites, secret and otherwise,

too voluminous to describe. “Ray has over 7,000

targets on his database. When I look at the GPS/Chart

plotter on his boat in the area off of LA/Long Beach, all

you can see is a one large mass of icons overlapping each

other. You can’t even see the underlying

chart,” Fabian says. But as Arntz puts it,

“collecting targets and identifying them are two

vastly different things.” Turns out the veteran wreck

hunter had also been looking for the elusive UB-88. The two

became good friends and joined forces in the hunt.

On July 9, 2003, Fabian headed out on his own (he says his

partner thought he had something more important to do that

day) to look at a single target that he’d spotted

during a fresh look at data already covered. “As soon

as I drove over it I knew it wasn’t a rock pile and

on the first camera pass I saw what looked like a shell

hole in the hull,” Fabian remembers. He and Arntz

returned to the site a week later to take a closer look

with the camera and that led to the dive expedition and

positive identification of UB-88 the following month.

Success followed 14 months of weekend searches and

investigation of over two-dozen targets, most of which

proved to be rock piles. The hunt for UB-88 has been

tremendously rewarding for Fabian. “Through it all my

only motivation has been to find a WW I German

U-boat,” he says. “There aren’t many

challenges like that around anymore.” Of the

accomplishment, he says: “it’s proved to be one

of the most satisfying of my life.” Editor